I did some refactoring of old code that started out as a Bash and Perl script. The idea was to fill a filesystem with random files of random content. The use case was to test filesystems and storage media. My code started out as C++ with some C to interface with the Linux® kernel’s syscalls. Essentially, it was an exercise into the wonderful world of the virtual filesystem layer (VFS), I/O options, memory attributes, and getting lots of random data faster than any disks could write. The random generator in the code comprises the SSE-accelerated Mersenne Twister algorithm from the University of Hiroshima. Clearly, this is a sign for pre-C++11 code. Modern code can use the C++ <random> library, which also uses SIMD instructions heavily if compiled in native mode. The works fine and has been used to test I/O performance and storage media. The problem: The SIMD instructions are for the Intel®/AMD™ platform only. What about ARM and RISC-V processors? Alternative processors use less power and enable to run the code on a smaller platform.

The code itself is mostly portable. When compiling for Microsoft® Windows® or Apple OS X, you can safely remove the Linux® syscalls. Basically, it is just madvise(), posix_memalign() and posix_fallocate64() to give the VFS layer some hints. C++11 and later standards allow for replacing the SSE MT random generator with the standard library. The first stage of refactoring was a hack, because I just redefined missing functions with empty function declarations. Don’t do that in production code, because it produces source code that you just don’t need on a specific platform. The next step is to collect all the platform-dependent code in classes that handle the interface and the random data generation. Alternatively, the random file could be its own class and instance, but this would cause more memory allocations. The current uses a single memory buffer to prepare the file content before the data is written to the file. Memory buffer size can be increased increased to 2 GB which shows nice alternating processor / I/O cycles. The code does not use any parallel code, so one memory buffer is fine.

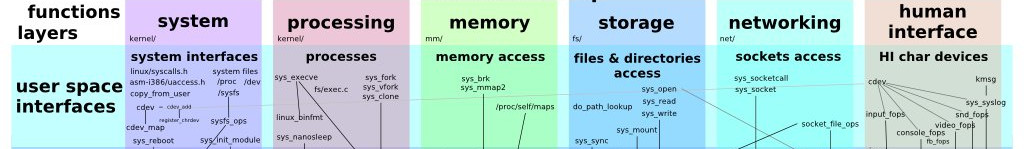

The code’s file I/O layer is very close to the Linux® kernel. open(), write(), and close() are called direct. madvise() is used to tell the kernel that the data will be written sequentially and that it will not be needed for reading soon. This helps the memory management. When combined with O_DIRECT, the code can run on desktops without filling up file and block buffers with write-only random data. This part is hard to refactor to C++’s stream library. I can recommend anyone to study the parameters of the syscalls I mentioned. Using the lower layers of the I/O subsystem can actually be useful in low-powered systems or when saving memory/performance. The uses of the code since 2008 have shown that the storage media and the I/O bus path to the device is the bottleneck. Both the SSE MT random generator and the C++11 <random> code can create more than enough data to saturate the I/O system.

The takeaway from writing cross-platform code is not surprising. Contain all the platform-dependent code in classes of functions. Do this early in your process, even in prototypes. Using empty functions to disable non-existent syscalls might be optimised away by the compiler, but it makes the source code messy. You will need some #ifdef / #ifndef directives, though. Best to collect them in your include files. If you are interested in the code, let me know. You can also use it for fuzzing, because there is a switch to create file and directory names from fully random bytes.